Last week I attended the LearnLab summer school at Carnegie Mellon University. The focus of the summer school was to teach students about learning sciences theories and methodologies, both through readings and hands-on work. Over the week, I learnt a lot about theorethical foundations in the learning sciences. As a note-to-self, and maybe a resource for you, below, I'll elaborate on the theories presented and how they can be incorporated in research.

Some interesting facts

First, I'll present some interesting tidbits that were central to all of the material in the course.- To learn something, you must do it. Active learning is essential.

- There are three types of knowledge: Syntax, Semantics and Pragmatics.

- The first question of each type is much harder than the later ones because it involves planning an answering strategy.

- Treat your teaching as research: teaching needs to be a community-based research activity instead of a solo sport.

- Impact of research can be increased by sharing data. Things to keep in mind are standardized formats, such as progsnap2 and PEML, and data repositories such as DataShop.

- Experts are only able to verbalize up to 30% of their knowledge, the rest is implicit knowledge, tacit skill.

Now, let's move onto the theories.

Knowledge Components and Learning Curve Analysis

source: Koedinger, K. R., Corbett, A. T., & Perfetti, C. (2012).

Knowledge Components are part of the KLI framework which is discussed in more detail below. However, I want to reflect on them individually too, as they return in many of the theories discussed in this blog.

According to Koedinger et al., Knowledge components are defined as:

Koedinger et al. identify types of KCs over two dimensions: the dimension of application, and the response dimension. Both of these can be constant or variable. Constant means that the KC is associated with a single unique pattern, whereas variable means that it might fit to multiple patterns. The three defined KC types are:

- Constant-constant. These are elements such as associations and facts, or more concretely, these can include vocabulary and tables of multiplication.

- Variable-constant. These include categories and concepts, such as knowing which grammar- and mathematical rules to apply. The elements that they are applied to are variable, but the outcome is predictable (the use of the rule).

- Variable-variable. These are the most versatile, they include skills, plans and models. One example is that of hypothesis testing.

Knowledge Components are central to the KLI framework, but how do we identify individual ones? This is a really hard task. For example, one might think multiplication and subtraction are elementary elements and thus should be KCs. However, there are other factors that influence this difficulty: can we just multiply left to right, or should we incorporate order of operations rules. Is our subtraction one that is positive, or will our result be in the negative numbers?

More specifically for Computer Science, code tracing can help us understand understanding. The core feature that can help us identify KCs are learning curves. These are graphs made based on student performance over a sequence of exercises. If the set of exercises captures only one KC, the performance should go up. If we see strange patterns in the learning curve, it is possible that we have not decomposed our KCs enough.

Conclusion: Trying to model Knowledge Concepts for programming languages seems like a very interesting challenge. During the summerschool, my partner Jawwad and I started trying this for simple SQL query formulation. I look forward to working on this in more depth, and would be happy to find collaborators to do so.

Jawwad and myself presenting our work at Friday's poster session. Photo credit: Caitlin Lim.

Jawwad and myself presenting our work at Friday's poster session. Photo credit: Caitlin Lim.

The Knowledge-Learning-Instruction (KLI) framework

source: Koedinger, K. R., Corbett, A. T., & Perfetti, C. (2012).

The article on the KLI framework was one of the largest preliminary readings that was offered for the summer school. With over 40 pages, it is quite the task. However, it was one of the most interesting things I learnt about this week.

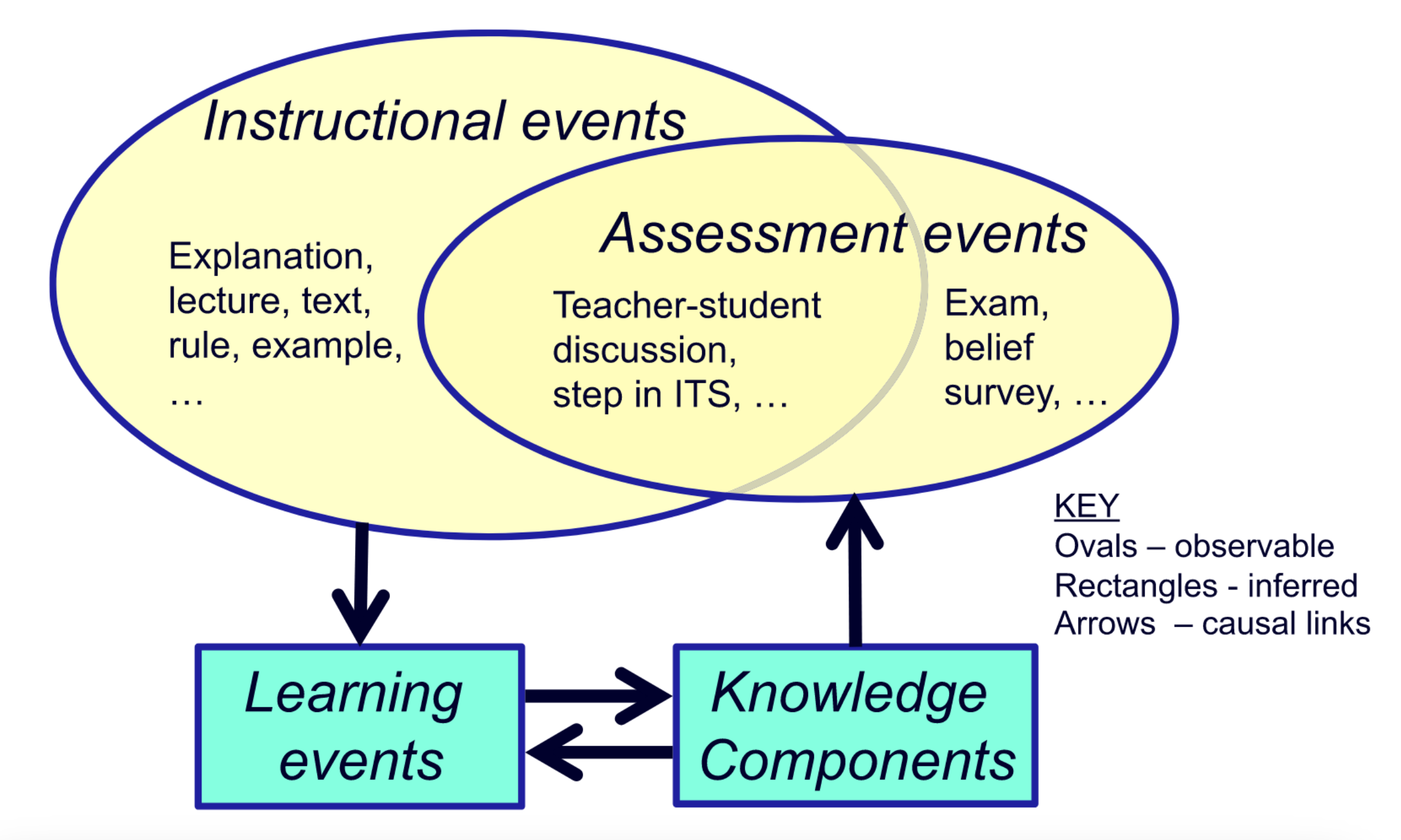

One thing we should realize about learning is that it is done in the brain, and we cannot observe this process directly. Instead, we can build models that connect learning to real-world, observable, phenomena. The KLI framework is built surrounding this principle.

The KLI framework relates a set of observable and unobservable events: learning events (LEs), instructional events (IEs), and assessment events (AEs), which are related through their associated Knowledge Components (KCs). Diagram courtesy of Koedinger et al.

The KLI framework relates a set of observable and unobservable events: learning events (LEs), instructional events (IEs), and assessment events (AEs), which are related through their associated Knowledge Components (KCs). Diagram courtesy of Koedinger et al.

The framework identifies 30 different learning principles related to teaching and instruction. These are in three categories:

- Memory and fluency. This category contains principles such as spacing vs. cramming, and scaffolding vs. no scaffolding.

- Induction and refinement. This category contains principles such as worked examples vs. normal questions, and interleaving vs. block practice.

- Sense-making and understanding. This category contains principles such as multimedia vs. plain text, and redundancy vs. no redundancy.

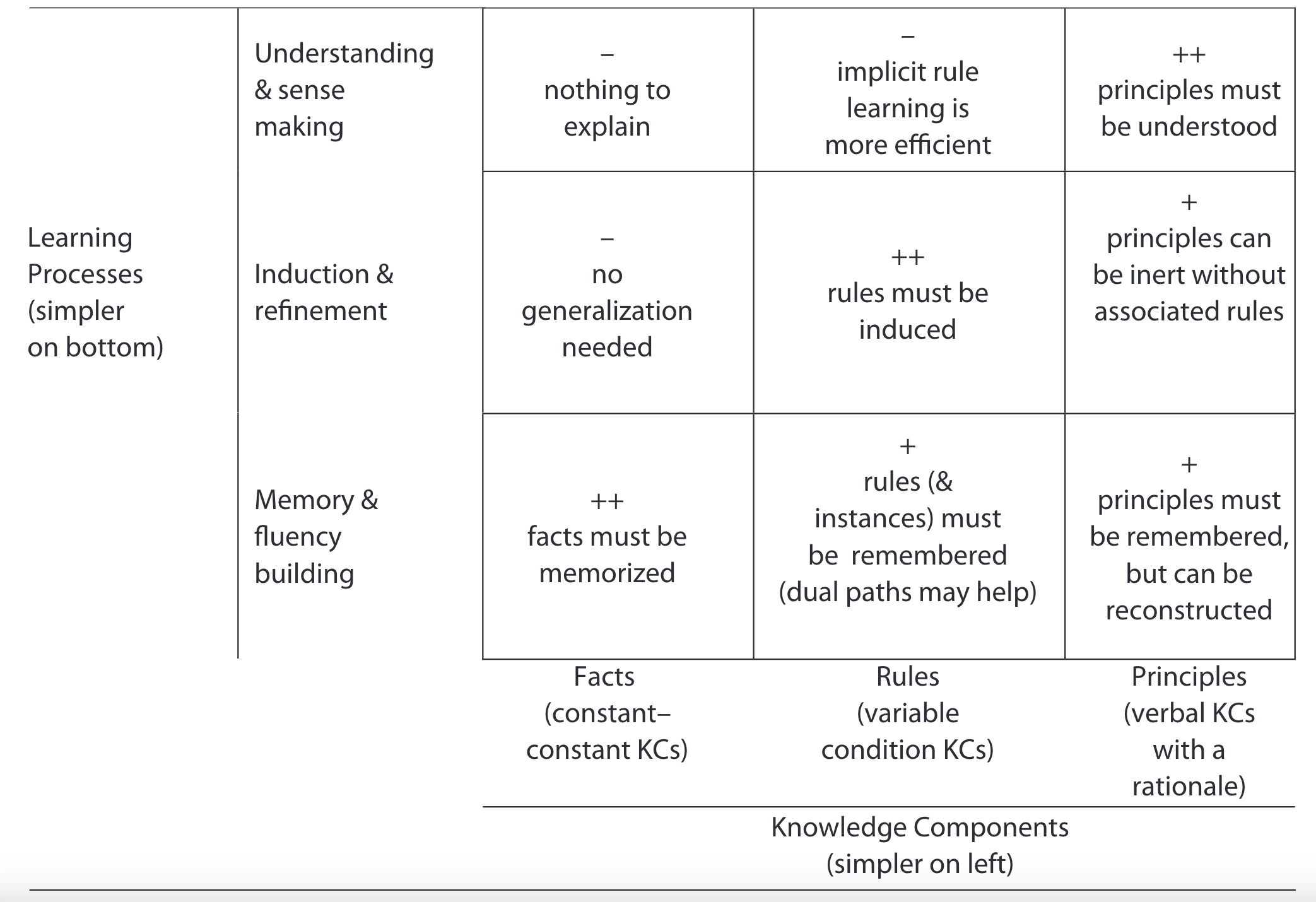

Given all these different principles, there are millions of unique combinations of instruction: instructional complexity. The KLI framework aims to identify those should always work well: instead of targeting by domain, they target based on the Knowledge Component type as discussed above, as well as on which Learning Event we want to reach.

Interestingly, the framework shows that applying more advanced learning techniques may have a negative influence on students' learning of simpler KC types. The most optimal learning effect is accomplished when the involvement of the learning event matches the difficulty of the knowledge component.

The diagram shows which types of learning processes are a good match for which types of KCs. Diagram courtesy of Koedinger et al.

The diagram shows which types of learning processes are a good match for which types of KCs. Diagram courtesy of Koedinger et al.

Conclusion: This seems like an important finding to keep in mind: we can design highly involved instructional materials, but if they do not match the difficulty of the concepts we are teaching, this work is wasted. So, appropriate educational design requires us to know more of the knowledge components that we are trying to teach.

Cognitive task analysis (CTA)

Cognitive task analysis means that we try to understand the cognitive processes of a learner while they are completing some task. There are many different ways in which we can do this, for example: structured interviews of experts, theoretical analysis, think alouds, difficulty factors assessments, learning curve analysis.

Theoretical task analysis specifically is very interesting, as it allows us to create a direct model which we can then test. The steps are as follows:

- Choose one specific task, such that the model is specific.

- Identify the starting state: what is the question?

- Identify the goal state: what does the answer look like?

- Unpack into intermediate states. For example, to be able to make a visualization, one needs to explore which types of variables are in the data.

- Iterate over point 3 as often as possible.

We can also use think-aloud studies to develop a model, or use think-aloud to try to confirm the model we developed before. To do so, we try to mark each of the lines in a transcript with subgoals for the CTA. Are there any goals that students are skipping? Are there extra subgoals that we have not included? If we can iterate over the model enough, we can build a theory of cognition for the task.

Conclusion: CTA might be able to help us identify the appropriate KCs to focus on in education. All of these theories are related and interconnected.

Adaptivity Grid

Source: Aleven, V., McLaughlin, E. A., Glenn, R. A., & Koedinger, K. R. (2017). Instruction based on adaptive learning technologies. In R. E. Mayer & P. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction (pp. 522-560). New York: Routledge.

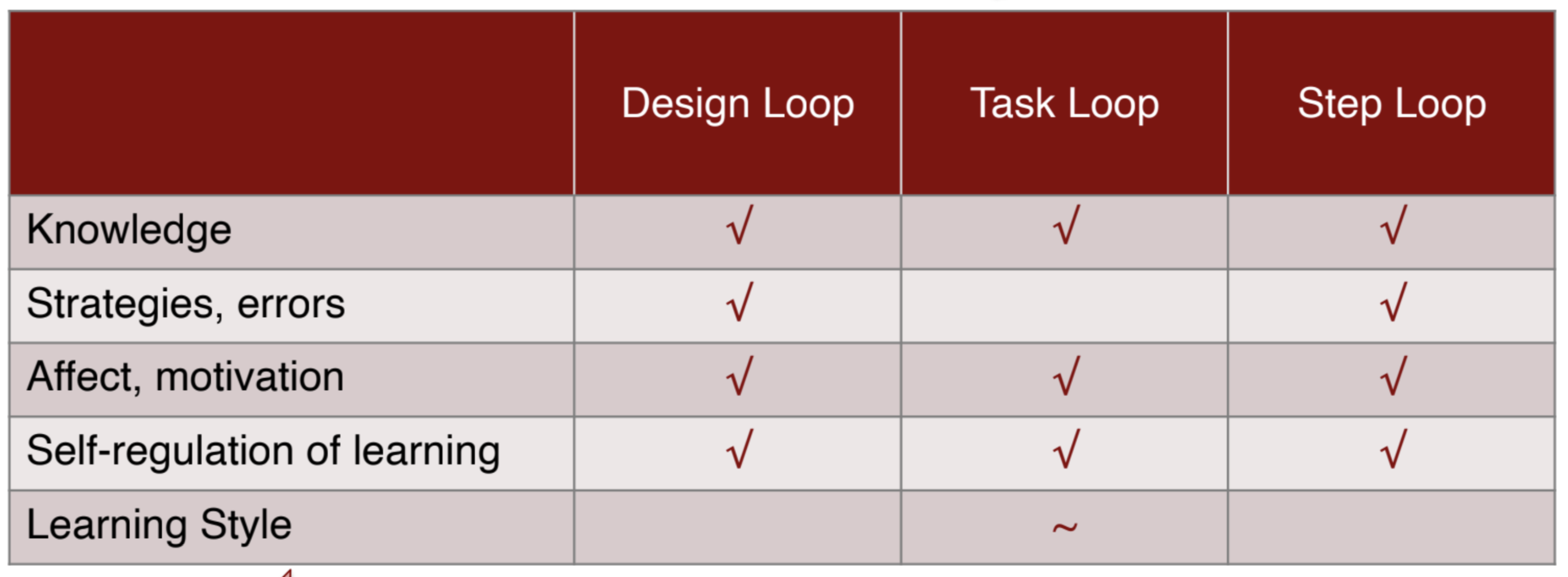

Instruction is the most effective when it takes into account that learners are different, and that they change as they learn. There are many aspects to learners and learning that we can adapt to: knowledge, strategies and errors, affect and motivation, self-regulation fo learning, learning styles. This, in combination with what we can adapt: design, tasks, and steps, leads to the adaptivity grid.

Most of the cells in this table are filled. That means that there have been interventions that have tried this adaptation. All of these have found some positive effect, with the exception of adapting to learning style. Diagram courtesy of Aleven et al.

Examples of adaptivity include:

Most of the cells in this table are filled. That means that there have been interventions that have tried this adaptation. All of these have found some positive effect, with the exception of adapting to learning style. Diagram courtesy of Aleven et al.

Examples of adaptivity include:

- For adapting to strategies and errors on the step level, we can provide students with step-level guidance. This could be feedback on correctness or hints for next steps.

- Adapting to knowledge on the task level can be done by analyzing cognitive mastery. To do this, students need to work in an intelligent system that records their progress on questions, and can measure which skills they need extra practice with. The system can then guide the student's practice.

- We can adapt to self-regulation of learning on the design level, by redesigning our smart learning systems to also gather students' reasoning on their answers. For example, for each step of the problem they solve, the student should add why they solved it as they did. Coming up with arguments helps the student understand how well they know the concept. Additionally, such reasoning may also help the student transfer knowledge correctly.

Conclusion: There are many more ways to adapt to student learning than I had ever thought possible. There is a wealth of things to still learn in this area.

Worked examples and faded scaffolding

The idea behind worked examples came from the application of cognitive load theory in education. If we know that students struggle to understand both the problem and the problem-solving method at the same time, we can provide them with worked examples: step-by-step solutions and explanations for a problem. The idea is that using worked examples, students should require less extraneous load, which means that they have more resources to process information, helping them learn more.

The concept of faded scaffolding takes this further. Students are supposed to learn from the worked examples, building some sort of step-wise solution model related to the task. Faded scaffolding means that the worked examples stay, but instead of showing the same thing over and over, they start dropping the explanation for final steps. This means that the student needs to perform the final steps themself. Withdrawing support further incrementally, means that by the end, the student fully knows how to solve the problem, without suffering from high cognitive load.

Conclusion: I like how worked examples and scaffolding take away some of the problems that students might have given cognitive load. Cognitive load is a very commonly mentioned program surrounding my work in SQL query formulation as well. During the LearnLab week, Jawwad and I drafted two worked examples for SQL. I see much promise in this direction for providing strong, clear examples to our students. In my misconception work, I found that students may have learnt query templates that they then apply incorrectly. If we can develop enough appropriate worked examples, this problem may also be reduced.

Closing

In conclusion, I have learnt a lot during the week of summer school. I fully recommend students and others working in CER to attend LearnLab. The new insights, both regarding theory and practice will hopefully prove valuable in the coming years. I leave Pittsburgh with my brain full of new ideas and research questions, as if I did not have enough of those already... To be continued!